Building a Machine Learning-Based generals.io Bot - Part 2

Exploring neural network approaches to an online strategy game

This is part 2 of our look at developing machine learning models for generals.io. If you missed the first part, you can read it here.

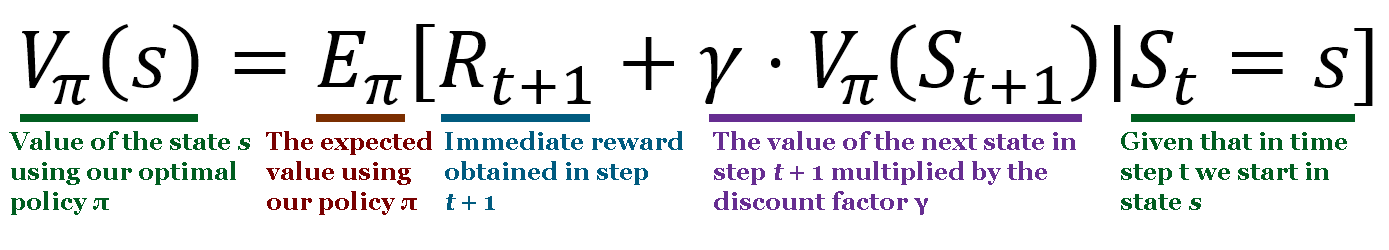

The Bellman Equation

What exactly is the Bellman equation? If you're familiar with dynamic programming, the Bellman Equation will feel very familiar, even if you've never seen it spelled out before, as Richard Bellman also developed dynamic programming.

Let's imagine we're a bot playing a game of generals.io and we're deciding what move we should make. We know all of the possible moves that we can make and our current estimate of the value of each possible state that would result from those moves. The optimal policy is to choose the move that results in the state that has the highest estimated reward. Once I choose that move, though, how do I update my previous estimate of my current state's value? And once I've won, how do I improve the reward I associate with all of the moves I made to get there? That's where the Bellman Equation comes in handy.

Here, Vπ(s) represents the value associated with a state s, γ (gamma) represents a discount factor, and Vπ(St + 1) represents the value of the next state. Every iteration, we can update Vπ using this equation to improve our value function. As the number of iterations (games, in our cases) goes to infinity, the value function will converge. The challenge of generals.io, though, is that the state space is huge and it's not feasible to explore the entire state space.

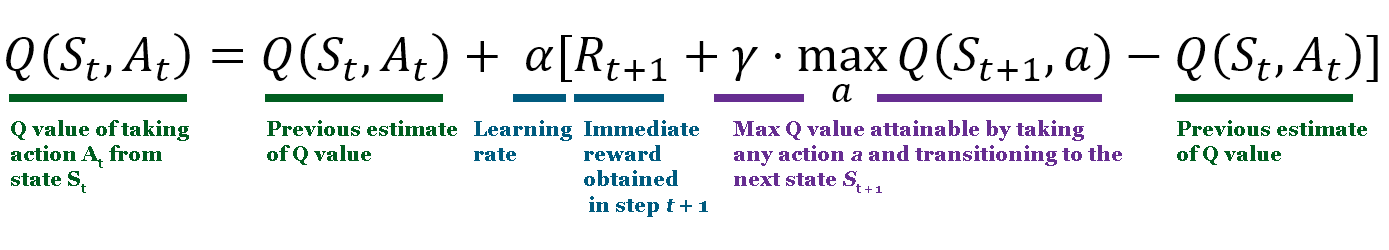

Q-Learning

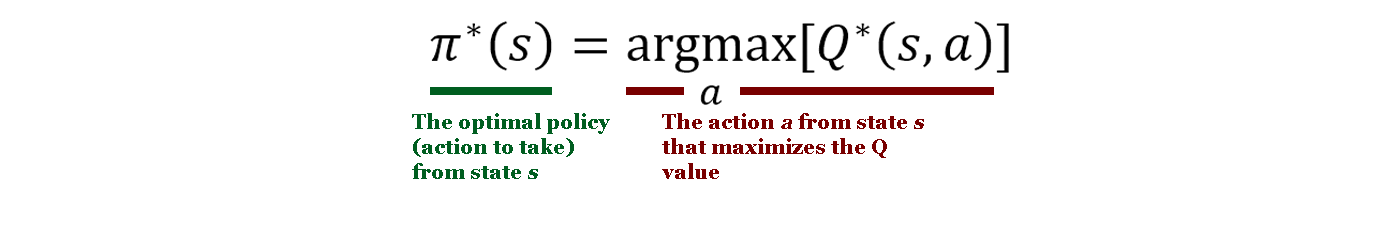

Q-Learning takes some of the ideas we saw in the Bellman Equation and provides an algorithm through which we can learn a policy. Just like before, we have a state s and actions a that we can use to move between states, earning a reward R by doing so. At the start of the Q-Learning algorithm, we create a table with pairings of every possible state and action and initialize it with a value, usually zero. We then move through the state space, updating Q values using the equation below.

See how the idea of maximizing future discounted reward is similar to the Bellman Equation? Once we've trained for long enough and our Q values have converged (and are no longer changing very much with each update), we can produce a "greedy" policy that always chooses the action that produces the highest Q value in the next state.

In this application, though, things are slightly more complicated. Because the state space of generals.io is so large (imagine all of the possible board combinations!), the bot can't just make a table to hold all of the possible states and actions. Additionally, initializing the Q table with zeros would likely start training with a bot that would struggle to earn any positive reward at all. Speaking of reward, what should the reward function be for a game of generals.io?

Instead of initializing the Q table with zeros, I used the results of the initial training epochs as described above. That way the bot won't have to learn entirely from scratch and I can save a lot of time training. What about estimating the value of the Q-value of the next state, since the bot doesn't have a Q table? Here's where I take a shortcut to save a ton of computation. I assume that the optimal future is always a 100% probability of victory, meaning that Q(St + 1, a) will always be 1. It's a little hacky, but computing the value of every possible subsequent state just isn't feasible. For a reward function, I use +10 if the bot is victorious, else -10. This reward results in meaningful changes to the Q value without maxing out the sigmoid activation function to 1. I also apply a discount function to the reward, so earlier turns are rewarded less than the turns leading up to the victory.

Advanced Models

CNNBrain has an advantage over MetricsBrain in that it can learn convolutional filters allowing it to interpret all sorts of different board states, but it doesn't change the fundamental fact that like MetricsBrain it can only look one move at a time into the future. That meant that the bot wasn't really acting with much long-term strategy in mind. Because so much of generals.io is dependent on making multiple coordinated moves in a row (think making a charge to capture an enemy general), this was fundamentally limiting the bot's performance.

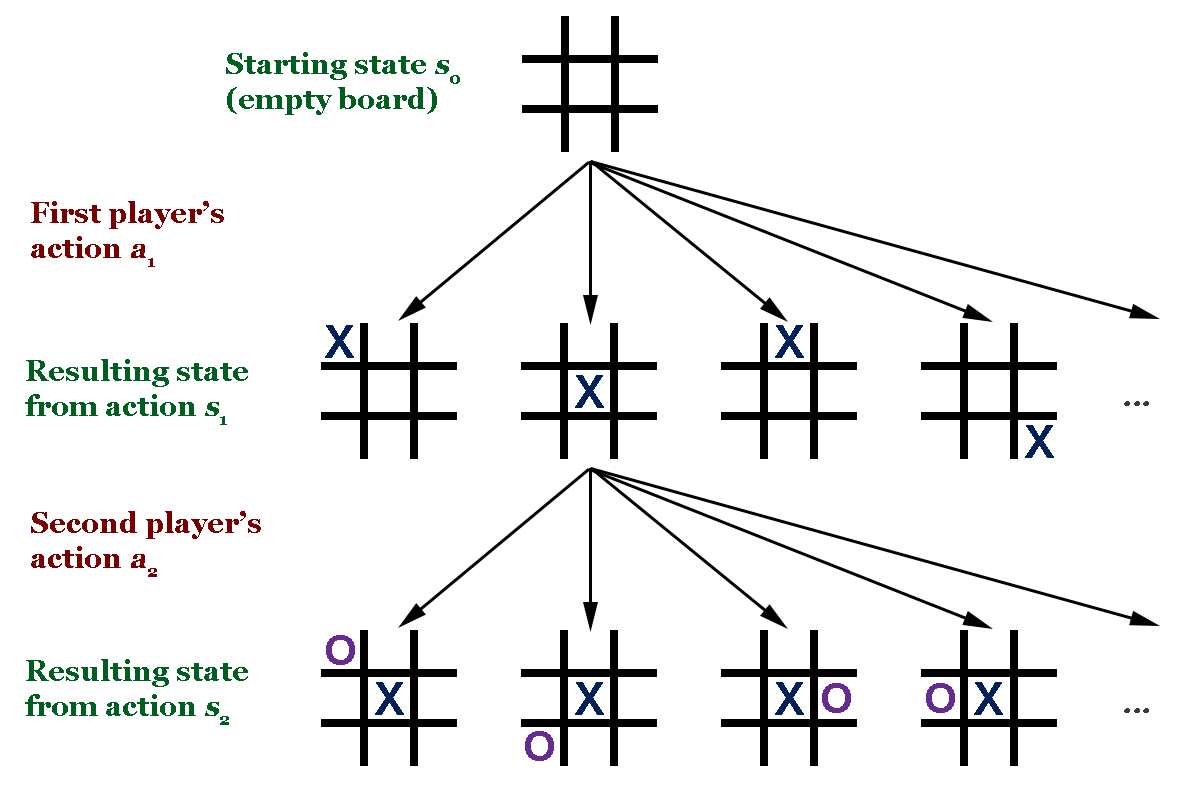

My strategy to address this was to implement a form of Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). In MCTS, the root node is the starting state of the game. All possible future ("child") moves are simulated, then future moves from those starting states are simulated, over and over until an end state is reached in every branch of the tree. Every node in the tree has an associated value (usually the win/loss rate). The key idea is that the algorithm anticipates opponent behavior and simulates future moves so that an ideal move (one that maximizes the win rate) can be selected.

MCTS is relatively straightforward in an application like tic-tac-toe where the state space is very limited and all future moves can be easily computed. What if it isn't possible to compute all of the possible states? For reference, tic-tac-toe has a state-space complexity of about 4 on average, chess is 43, and Go is 172[1]. That means that every node in the tree will have roughly 4 children in tic-tac-toe and 172 in Go, meaning after 3 moves the tic-tac-toe tree will have ~256 possible states and Go will have 5,088,448. I would estimate that generals.io has a state-space complexity similar to that of Go if not higher. How should the algorithm select nodes to explore in that sort of complex environment?

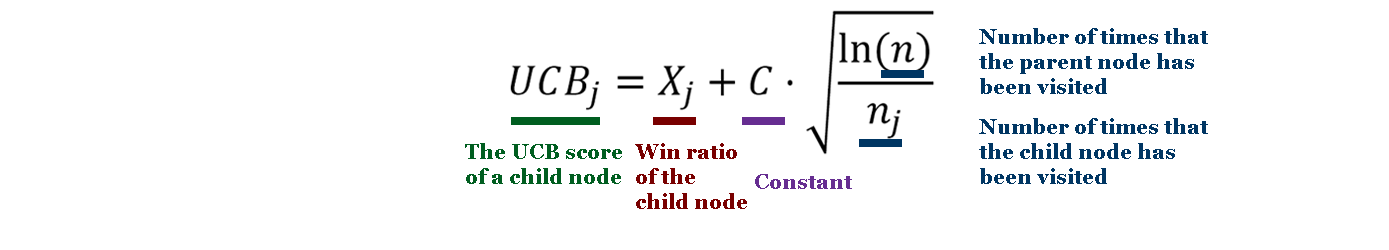

Fortunately, Go has motivated work on that exact question. One technique, called Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) or Upper Confidence Bound Applied to Trees (UCT), introduces a simple mathematical way to balance exploration (vising nodes that don't appear to be ideal) versus exploitation (visiting the nodes that appear best).

Here, Xj is the win ratio of the child node, C is an constant used to weight the exploration factor (set to sqrt(2) in the original paper), n is the number of times that the parent node has been visited, and nj is the number of times that the child has been visited. When choosing a child to explore, the node with the highest UCB score is chosen. Implementing UCB results in a search that explores more often when the child nodes have not been visited often, but as time passes transitions to exploiting the nodes with the best win percentage. This sort of strategy has been used in AlphaGo and almost all other modern Chess and Go engines.

I implemented Monte Carlo Tree Search with Upper Confidence Bounds in my bots and saw an immediate performance leap. The bots were now able to choose the best move with the future in mind. There were a few design decisions I had to make, though. Because turns are limited to 0.50 seconds, I had to balance exploration versus exploitation in a time-limited environment. I chose, then, to double the number of moves I could simulate by choosing not to simulate the opponent's moves. Most of the time, based on the state-space complexity and processing power available, the bot was able to look between 5 and 10 moves into the future. I didn't feel that any opponent move in that timescale was significant enough to warrant halving the number of turns I could simulate. I also spent a considerable amount of time tuning the parameters of my search to maximize its performance within the time constraints. Instead of a constant C, I implemented an adaptive time scaling factor that increased if the bot was looking more than 10 moves ahead (to encourage more exploration) and decreased if the bot was looking fewer than 5 turns ahead (to encourage more exploitation). I found that this helped balance performance in the early stages of the game, when there are fewer possible moves, and late in the game, when there are many possible moves.

Results

Adding MCTS immediately improved the performance of all of my bots. Because MCTS isn't model-specific, I could even use it in conjunction with MetricsBrain and other non-neural models. I started training via self-play with MCTS, and after 30 episodes of 5 game each, I started to see some noticeable improvement in the bots' performance. They started to increase their win percentage against MetricsBrain (without MCTS), which was the baseline level of performance.

150 total games isn't a huge amount of data, through. Despite the amount of time it took to train, that was a small fraction of the amount of data that I would anticipate making a big difference in bot performance. Further training and evaluation is an ongoing process, and I'll post any updates here as they come out.

Challenges

The first challenge I ran into after finishing my work was that the bot server was down, so I couldn't actually play against my bots myself. While I could see the results of local games between my bots, it wasn't quite the same as seeing how they stacked up against a human player. The site was down for about two months after I finished training my first round of bots, but as of the time this is published the site is back up.

My ability to train the models quickly was definitely a limitation. I was running all of this on my personal laptop, and every epoch (in which the bots played 5-10 games and trained on the resulting moves for 20 epochs) took around 30 minutes of max VRAM usage. I made some optimizations to the Board class as a result, and while it reduced the training time by around 25% it didn't change the fact that I was spending a lot of time waiting for models to train.

Another problem I ran into was the time it took to train via self-play. Games played locally used the same 0.5 second turns that games online use in order to best replicate the environment, so a 200-turn game would take at a minimum 100 seconds to play through and then another ~30 seconds to actually train the model on the moves. One way forward could be to change the training environment completely and explore as much of the state space of a single game as possible. That could help the model learn a good Q function without having to play new games over and over.

Lastly, there are still some bugs that creep up in my implementation of Board from time to time. Sometimes the attacking logic doesn't work as intended and armies and/or territory are incorrectly awarded. Despite spending a sizeable amount of time and effort trying to track this down, I haven't been able to yet. Unfortunately, that's partly due to the complexity of the Board class as it now contains almost all of the game logic.

Current Work

As mentioned above, one promising avenue is allowing the bot to self-play one game in great depth, exploring many possible moves without a time constraint. I believe some pruning of useless moves will still be necessary, though, given the huge number of states that can result after just a few moves.

More work can be done to explore different types of bots as well. I used CNNs with a Q-Learning approach, but RNNs are also well suited to this sort of task. There are many, many different ways to go about creating features from the game board and processing that data. I'm excited to see what people can come up with!

Project Links

The GitHub repository has all of the code I used in this project. The README has some basic instructions if you're interested in running the code yourself. Enjoy!

About

In this article, we take a look at the process of creating neural network-based players for the game generals.io. This is part 2 of 2 (previous).