Using Decision Trees to Predict Hall-of-Fame Batters

What makes a player great? Predicting future Hall-of-Fame batters using machine learning.

The Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, had held an induction ceremony every year since 1961. Like so many events and ceremonies this year, though, this year's ceremony was postponed to coincide with the 2021 ceremony. Larry Walker, Derek Jeter, Ted Simmons, and Marvin Miller will be enshrined next summer. But who will be inducted alongside them?

Predicting future Hall-of-Famers is a hobby almost as old as the game itself. The Baseball Writer's Association of America (BBWAA) voted on the first class in 1936, selecting Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Matthewson, Babe Ruth, and Honus Wagner. Since then, 329 players have joined them in Cooperstown. There are a couple of different avenues into the Hall:

BBWAA voters may cast a vote for up to 10 players each year. To be elected, a player must receive at least 75% of the vote. Players are eligible after 5 years of retirement, and to appear on the ballot they must have served at least 10 years in the majors. 131 players have been inducted this way.

Four committees, commonly referred to as the Veterans' Committee, select players that were not otherwise inducted by the BBWAA vote. These include Early Baseball (prior to 1950), Golden Days (1950 - 1969), Modern Baseball (1970 - 1987), and Today's Game (1988 - present). These committees meet at different frequencies, with the Modern Baseball and Today's Game committees meeting twice every five years, the Golden Days committee meeting once every five years, and the Early Baseball committee meeting once every ten years. The threshold is 75% of the vote, similar to the BBWAA vote.

All of these voters are looking for one intangible thing: greatness. What makes a player great? Of the tens of thousands of people that have ever played on or managed a professional baseball team since the beginning of organized play in the late 1860s, only a few hundred have been enshrined in Cooperstown. Without any other information, that gives a new player a less than 1 percent chance of making the Hall. Baseball is a numbers game, though. Ask even a casual fan and they'll be able to name a few statistical markers of an extraordinary player - 3,000 hits, 500 home runs, or 3,000 strikeouts. We should be able to use those markers to reasonably predict a player's chances of making the Hall of Fame, right? Even better, can we do it with machine learning?

The Problem

Using all of the data available about historical players, can we predict which eligible players will be inducted into the Hall of Fame in the future? In our list of eligible players, we'll include both players that have played within the past five years (and so do not meet the ballot's criteria) and players that have appeared on the ballot but haven't reached the 75% threshold for induction.

Decision Trees

Within the field of machine learning, there are a lot of models to choose from. Some, like neural networks, have a lot of expressive power, meaning they can model very complex relationships between inputs and outputs. Decision trees, on the other hand, can be relatively simple. Fundamentally, a decision tree is a tree of nodes. At each node, a decision is made about the data, and a different path is taken depending on the result. At a leaf node, the model assigns a prediction to the data. They have the property of being very easy for a human to interpret: to understand why the model made a certain prediction, we can just follow the data through the series of nodes until we reach a leaf node. While explainable AI is an interesting field in machine learning, neural networks and other models just don't have that same level of explainability. That's why we'll use decision trees to make our predictions about the Hall of Fame.

Other Problems

In order to do this, of course, we need to collect data on all of these players. Luckily, the Chadwick Bureau Baseball Databank makes this easy. It has compiled statistics on almost every aspect of the game imaginable dating back to the 1870s. We'll select out just the batting data for this project.

As mentioned before, a very small percentage of players ever make the Hall of Fame. If our model just predicted 'No' every time we wanted to guess whether a player would make the Hall of Fame, it would have an accuracy of around 99%. Obviously, that's not as good as it looks. This problem is called having imbalanced classes. To fix this, we can increase the size of our set of Hall of Fame players by duplicating the entries. This is called upsampling. Even if we increase the size of our Hall of Fame sample by just two or three times, it will significantly improve performance.

Instead of a simple accuracy metric, we can also use another metric, called AUC-ROC. It solves the problem of being able to blindly guess 'No' and achieve a 99% accuracy score. AUC, meaning "area under the curve", balances the weight given to true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. We'll use the AUC-ROC score to give a better estimate of the model's performance.

We also want to prevent our model from overfitting the data. Overfitting is when a model starts to see patterns in the training data that don't actually help it generalize to new data. When a model overfits, we can see its training performance improve at the expense of testing performance. With decision trees, we can set a minimum threshold for the minimum amount of impurity - that is, the percentage of mistakes that a node makes - that a node must have for it to make another split. That ensures that our model makes the most generalizable predictions possible on our test set. Additionally, we'll limit our decision tree to a maximum of four levels. Like the minimum impurity decrease threshold, this option ensures that our model won't overfit to the data we train it on.

Results

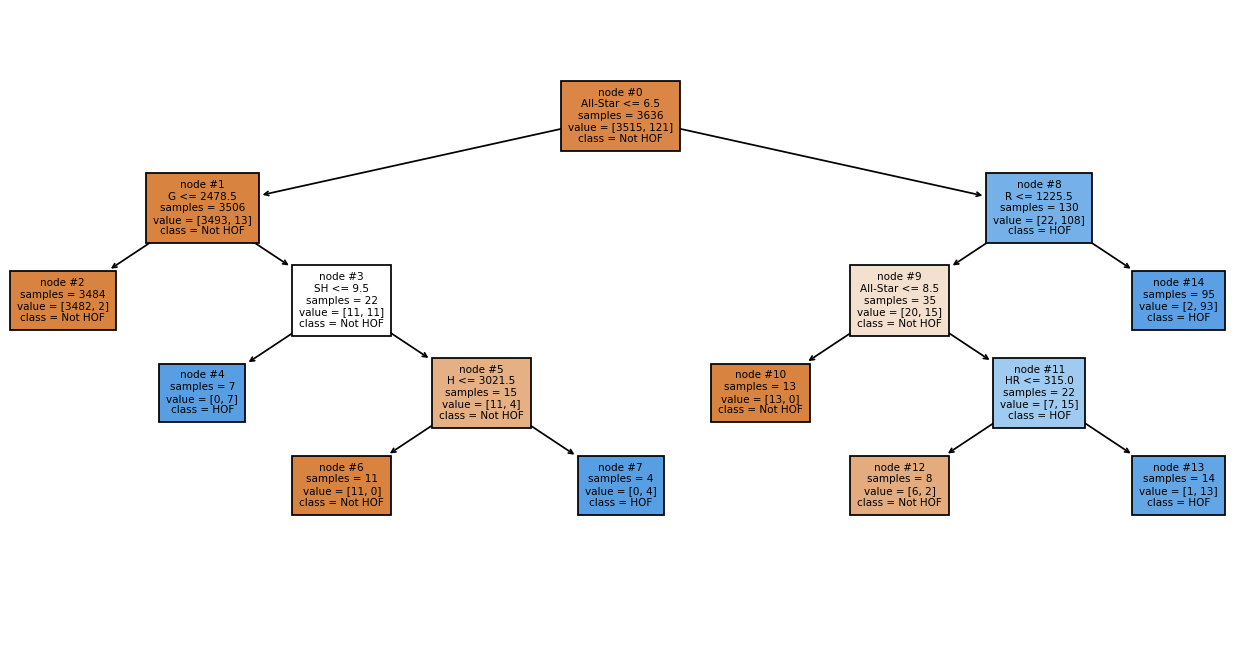

All of the code used in this article can be found here. First, let's take a look at our model.

Starting from the top, the first node splits the data based on the number of All-Star appearances in a player's career. Players with 7 or more appearances go to the right, while players with less than 7 to go the left. With just one split, the data is already divided into majority-HOF and majority-non-HOF classes. Looking down the rest of the tree, we can see that the number of games played and the 3,000 hit marker help sort out Hall-of-Famers in the left side of the tree, while a player's number of runs scored and their career home run totals are among the splits used in the right side.

On an intuitive level, this seems reasonable - All-Star Game appearances are a good overall indicator of a player's level as compared to the rest of the League, and having multiple appearances suggests that a player performed at an elite level over the span of several years. Other nodes, like career home runs, are those universal statistical markers that all fans have in mind. The nodes that split based on games played and runs scored are good indicators of career length, which is another requirement for admission into Cooperstown.

Even more interesting than the players that the model correctly classifies are those that it makes mistakes on. First, let's take a look at the players that our model predicted would be in the Hall of Fame, but aren't:

| Name | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | SO | IBB | HBP | SH | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mark McGwire | 1874 | 6187 | 1167 | 1626 | 252 | 6 | 583 | 1414 | 12 | 1317 | 1596 | 150 | 75 | 3 | 0.263 | 0.394 | 0.588 | 0.982 |

| Dave Parker | 2466 | 9358 | 1272 | 2712 | 526 | 75 | 339 | 1493 | 154 | 683 | 1537 | 170 | 56 | 1 | 0.290 | 0.339 | 0.471 | 0.810 |

| Pete Rose | 3562 | 14053 | 2165 | 4256 | 746 | 135 | 160 | 1314 | 198 | 1566 | 1143 | 167 | 107 | 56 | 0.303 | 0.375 | 0.409 | 0.784 |

Mark McGwire's on-the-field achievements are worthy of consideration for enshrinement in Cooperstown - 583 home runs, 12 All-Star Game appearances, and a career OPS+ of 163 - but his admitted steroid use prevented him from receiving more than 25% of the vote, and he fell off of the ballot in 2016.

Dave Parker is an interesting case. He meets our model's thresholds of at least 7 All-Star Game appearances and at least 1226 runs, so we predicted that he would be in the Hall of Fame. He was on the Modern Era Committee's ballot in 2020, where he received 43.75% of the vote. According to Baseball Reference, he has a JAWS of 38.7. This puts him right on the lower end of HOF-worthy right fielders, but still above other HOFers like 2019 inductee Harold Baines. For now, he's in the Hall of Very Good.

Pete Rose, like Mark McGwire, has a stat line worthy of the Hall of Fame. Over the course of his career, he amassed more games (3,562), at-bats (14,053) and hits (4,256) than anyone in MLB history. However, Rose was placed on Major League Baseball's ineligible list by mutual agreement in 1989 following an investigation into his gambling on the Reds. Although the Hall of Fame had informally prevented players on the ineligible list (like 'Shoeless' Joe Jackson) from being elected to the Hall, a 1991 rule made that rule official. When Rose became eligible for induction via the Veterans' Committee in 2007, it soon passed a rule barring players on the ineligible list from consideration. Rose's repeated petitions for reinstatement have all been denied, most recently by Commissioner Rob Manfred in 2015. Rose may make it in one day, but there are a number of things that need to happen before he can even appear on the ballot.

We can also look at the reverse - players who are in the Hall of Fame that our model predicted would not be.

| Name | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | SO | IBB | HBP | SH | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jeff Bagwell | 2150 | 7797 | 1517 | 2314 | 488 | 32 | 449 | 1529 | 202 | 1401 | 1558 | 155 | 128 | 3 | 0.297 | 0.408 | 0.540 | 0.948 |

| Bill Mazeroski | 2163 | 7755 | 769 | 2016 | 294 | 62 | 138 | 853 | 27 | 447 | 706 | 110 | 20 | 87 | 0.260 | 0.299 | 0.367 | 0.667 |

| Kirby Puckett | 1783 | 7244 | 1071 | 2304 | 414 | 57 | 207 | 1085 | 134 | 450 | 965 | 85 | 56 | 23 | 0.318 | 0.360 | 0.477 | 0.837 |

| Willie Stargell | 2360 | 7927 | 1194 | 2232 | 423 | 55 | 475 | 1540 | 17 | 937 | 1936 | 227 | 78 | 9 | 0.282 | 0.360 | 0.529 | 0.889 |

| Frank Thomas | 2322 | 8199 | 1494 | 2468 | 495 | 12 | 521 | 1704 | 32 | 1667 | 1397 | 168 | 87 | 0 | 0.301 | 0.419 | 0.555 | 0.974 |

| Alan Trammell | 2293 | 8288 | 1231 | 2365 | 412 | 55 | 185 | 1003 | 236 | 850 | 874 | 48 | 37 | 124 | 0.285 | 0.352 | 0.415 | 0.767 |

| Larry Walker | 1988 | 6907 | 1355 | 2160 | 471 | 62 | 383 | 1311 | 230 | 913 | 1231 | 117 | 138 | 7 | 0.313 | 0.400 | 0.565 | 0.965 |

Kirby Puckett and Bill Mazeroski have 10 and 12 All-Star Game appearances, respectively, so they meet our first criterion. At the home run test, however, they both fall below the threshold of 315 home runs. In Mazeroski's case, the real value he generated was on defense, where he earned 8 Gold Glove awards. Puckett, on the other hand, had his career ended prematurely by glaucoma and was a two-time World Series champion with the Twins. Those aspects of their careers - defense and championship hardware - aren't included in this model (although Gold Glove awards are included in the data). Purely based on their batting, our model doesn't think they would make Cooperstown, and that seems pretty reasonable.

Willie Stargell has 7 All-Star Game appearances and 475 home runs, but our model requires players with less than 1226 runs scored to have 9 or more All-Star Game appearances in order to be classified as a Hall-of-Famer. He ranks just slightly below the average Hall of Fame left fielder in JAWS. To me, though, Willie Stargell is a clear-cut Hall-of-Famer, especially because of his 1979 campaign in which he won the NLCS MVP, World Series MVP, and league MVP awards.

The rest of the players here don't have enough All-Star Game appearances or games played for our model to classify them as Hall-of-Famers. Like mentioned before, though, this model doesn't necessarily take a player's defensive value or position into account. Frank Thomas is one of the best designated hitters of all time, and Alan Trammell played Gold Glove-caliber defense over his 20-year career.

Overall, I wouldn't call any of these players (except for Stargell) locks for the Hall of Fame, but at the same time I don't think any of these players don't belong in Cooperstown. Then again, I'm not much of a 'small Hall' person.

Modern Players

With our model, we can now make predictions about eligible players:

| Name | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | SO | IBB | HBP | SH | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrian Beltre | 2933 | 11068 | 1524 | 3166 | 636 | 38 | 477 | 1707 | 121 | 848 | 1732 | 112 | 97 | 14 | 0.286 | 0.339 | 0.480 | 0.819 |

| Carlos Beltran | 2586 | 9768 | 1582 | 2725 | 565 | 78 | 435 | 1587 | 312 | 1084 | 1795 | 104 | 51 | 18 | 0.279 | 0.350 | 0.486 | 0.837 |

| Barry Bonds | 2986 | 9847 | 2227 | 2935 | 601 | 77 | 762 | 1996 | 514 | 2558 | 1539 | 688 | 106 | 4 | 0.298 | 0.444 | 0.607 | 1.051 |

| Miguel Cabrera | 2400 | 8949 | 1429 | 2815 | 577 | 17 | 477 | 1694 | 38 | 1135 | 1761 | 234 | 63 | 5 | 0.315 | 0.392 | 0.543 | 0.935 |

| Robinson Cano | 2185 | 8502 | 1234 | 2570 | 562 | 33 | 324 | 1272 | 51 | 607 | 1165 | 111 | 84 | 10 | 0.302 | 0.352 | 0.490 | 0.843 |

| David Ortiz | 2408 | 8640 | 1419 | 2472 | 632 | 19 | 541 | 1768 | 17 | 1319 | 1750 | 209 | 38 | 2 | 0.286 | 0.380 | 0.552 | 0.931 |

| Albert Pujols | 2823 | 10687 | 1828 | 3202 | 661 | 16 | 656 | 2075 | 114 | 1322 | 1279 | 311 | 107 | 1 | 0.300 | 0.379 | 0.549 | 0.927 |

| Manny Ramirez | 2302 | 8244 | 1544 | 2574 | 547 | 20 | 555 | 1831 | 38 | 1329 | 1813 | 216 | 109 | 2 | 0.312 | 0.411 | 0.585 | 0.996 |

| Alex Rodriguez | 2784 | 10566 | 2021 | 3115 | 548 | 31 | 696 | 2086 | 329 | 1338 | 2287 | 97 | 176 | 16 | 0.295 | 0.380 | 0.550 | 0.930 |

| Gary Sheffield | 2576 | 9217 | 1636 | 2689 | 467 | 27 | 509 | 1676 | 253 | 1475 | 1171 | 130 | 135 | 9 | 0.292 | 0.393 | 0.514 | 0.907 |

| Sammy Sosa | 2354 | 8813 | 1475 | 2408 | 379 | 45 | 609 | 1667 | 234 | 929 | 2306 | 154 | 59 | 17 | 0.273 | 0.344 | 0.534 | 0.878 |

| Ichiro Suzuki | 2653 | 9934 | 1420 | 3089 | 362 | 96 | 117 | 780 | 509 | 647 | 1080 | 181 | 55 | 50 | 0.311 | 0.355 | 0.402 | 0.757 |

With 20 MVP awards between them, this is a pretty solid list. Let's break it down, case-by-case:

Adrian Beltre: One of the best defensive third basemen of all-time, Beltre was a fan-favorite up until his retirement in 2018. He never made an All-Star Game in his twenties, but made up for it in the next decade. He'll be eligible for the Hall in 2024.

Carlos Beltran: He's had a long career and put up some solid numbers on the Royals, Astros, and Mets. Based on our model, the ASG appearances and runs scored are enough to punch his ticket. He was the alleged leader of the Astros' 2017 sign-stealing scandal, though, and soon after became the shortest-tenured manger in Mets history. He'll be eligible in 2023.

Barry Bonds: Oh man. He's an inner-circle Hall-of-Famer based on stats alone, but his PED use has put him on the Hall of Fame blacklist so far. He received over 60% of the vote in 2020 and is trending upwards, so there is still hope. It will have to happen soon, though - he slides off of the ballot in 2022.

Miguel Cabrera: Even though Miggy isn't retired, he could hang up his cleats today and walk into Cooperstown. Our model loves his 11 ASG appearances and 1429 runs scored, and real-world voters will love his 2 MVP awards and Triple Crown.

Robinson Cano: Cano has the numbers and falls into the same category in our model as Cabrera, but he also has an involvement with PEDs. The Hall hasn't historically been friendly to PED users, so Cano's case is a lot more complicated than it was just a couple years ago.

David Ortiz: If the greatest designated hitter of all time isn't Edgar Martínez, then it's David Ortiz. Ortiz, like some others in this list, has some association with PEDs, but he was never officially listed on that 2003 report. He has the ASG appearances and runs to make it in our model, and since he was never officially found guilty his path to the Hall is clearer than others'. His first appearance on the ballot will be in 2022.

Albert Pujols: The Machine is a lock for the Hall of Fame. 661 home runs, 3 MVP awards, and a 20-year playing career make him one of the best of the best. The only real question is whether he'll wear a Cardinals cap or an Angels cap.

Manny Ramirez: Manny is another player with HOF-level stats (12 ASG, 1544 R, 555 HR) and a dubious association with PEDs. Like Cano, he'll have to wait for the voters to get friendlier towards PED users. On top of that, he'll have to wait for some of the animosity that comes with being such a controversial figure to dissipate - but that's just Manny being Manny. He received 28.2% of the vote in 2020.

Alex Rodriguez: A-Rod, by the numbers, is one of the most impactful position players of all time. With 14 All-Star appearances, there's no doubt he has the numbers. Voters won't forget about his PED use, though. He's in the same category as Manny and Cano, and will first appear on the ballot in 2022.

Gary Sheffield: Sheffield, like many others here, is classified as a Hall-of-Famer by our model because of his 9 ASG appearances and 1636 runs. He hit over 500 home runs in his career as well. He was named in the Mitchell Report, though, linking him to PED use. He received 30.5% of the vote in 2020 in his sixth year of eligibility.

Sammy Sosa: With 609 home runs, 7 ASG appearances, and 1475 runs scored, Sosa is a HOFer by our model's standards, but with only 13.9% of the ballot in 2020 and 2 years of eligibility left it will be an uphill battle.

Ichiro Suzuki: Ichiro is an incredible talent and one of the best to play organized baseball. Counting his time in the JPPL, he amassed 4,367 hits - more than Pete Rose. He's a first ballot Hall-of-Famer in 2025.

As for what I think? I'd divide them into three categories: locks, likely inductees (despite controversies), and outsiders.

- Locks: Ichiro, Miggy, Beltre, and Pujols are all first-ballot Hall of Famers. Easy.

- Likely: I think Ortiz, who was never formally found guilty or suspended for PED use, has a good case and will make it on his third or fourth ballot. Beltran will make it, too - probably around his fourth or fifth try. Cano had already compiled a solid case for the Hall of Fame before he tested positive for PED-related substances in 2018. As a result, I think he has a better case than other PED-positive players and will make it eventually. A-Rod, like Cano, will benefit from changing attitudes in the BBWAA voters towards PEDs over the next decade. I think he'll make it, even if it's late in his eligibility.

- Outsiders: Bonds, Sosa, Ramirez, and Sheffield are all currently on the ballot. For Bonds and Sosa, it's now or never: they only have two years left. I don't think any of them have the percentages or momentum to make it in via the BBWAA vote. They'll have another shot via the Veterans' Committee, though, and I think it's likely they could make it in that way. For now, they're on the outside looking in.

Conclusion

The first test for any machine learning model is to make sure it matches human intuition. I'd say it passes this test pretty well. Some of its false positives were players like Pete Rose and Mark McGwire, who had off-the-field issues that prevented them from entering the Hall. None of its false negatives were particularly terrible. All of the eligible players that it predicts would make the Hall of Fame are reasonable. So far, so good.

There are, however, a few players that have good Hall of Fame cases that it didn't include. Yadier Molina has put together a great career at catcher for the Cardinals. Buster Posey, too, could be a Hall of Fame backstop. Our model doesn't think Molina has enough runs scored or home runs to be a Hall-of-Famer, but I think it undervalues the value of catchers.

As for the machine learning aspect of this project, our choice of a decision tree for this project allowed us to see exactly how it makes these predictions. Some of the markers it chose - like All-Star Game appearances - are in line with what most fans would expect. Others, like runs and sacrifice hits, are a little more surprising. Even with just 4 levels, though, it achieves a pretty high performance on this dataset. In the world at large, decision trees can be really useful in the medical field or in other fields where trust is centrally important. There are ways to improve the performance of these trees, too, like boosting and random forests.

Do you think this model missed anyone? Think you could train a better model? All of the code is provided in an annotated Google Colab notebook here. Remember, too, that this model is solely based on a player's batting performance. We'll do the same thing for pitching next.

About

In this article, we explore the use of decision trees to develop a classifier for MLB Hall of Fame batters and use that model to make predictions on active players.